Women’s History Month

March is Women’s History Month, and, during this time of celebration, it is important to acknowledge the crucial part that women have played in forming our society. Women have advocated for the right to vote, led major social movements, and been at the forefront of almost every historical change.

Women’s Suffrage Movement

What is suffrage?

Suffrage is a concept that describes a person’s capacity to take part in society through their ability to cast a ballot in elections.

Importance of Voting

Voting is crucial because it represents every citizen’s voice, and that voice enables each to express their views on issues that are important to them and how they believe their lives should be lived. Voting is the way individuals express the ideas they support, the political party they want to represent them, and the candidate(s) they believe will make their lives better, as well as enhance the experience of their community and community members.

The Fight For Suffrage

One of the most well-known movements in history is the fight for suffrage. Women across the United States and Europe joined forces to generate change. One of the changes sought was granting women the right to vote.

The Beginning

While we often hear about the leaders of this movement, like Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who started everything in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention, with her Declaration of Sentiments.

Over the next almost 70 years, there would be countless other women who made a significant impact. Alice Stokes Paul and Lucy Burns are two examples.

Alice Stokes Paul

“When you put your hand to the plow, you can’t set it down until you get to the end of the row.”

Alice Paul was the oldest of Tracie Parry and William Paul’s four children. She was born on January 11, 1885, in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, into a Quaker family.

Her father was a wealthy businessman, and her mother was a suffragist. They subscribed to gender equality and education for women, and they worked to improve society. As a child, Alice’s mother took Alice with her to women’s suffrage meetings.

Alice graduated in 1905 with a degree in biology from Swarthmore College (a Quaker institution that her grandfather helped co-found). She studied at the New York School of Philanthropy, which is now Columbia University, and graduated in 1907 with a Master of Arts in sociology. After studying social work in England for a year, she returned and received a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1910.

She was a well-educated, no-nonsense, blunt-speaking woman. Paul dedicated her life to women’s equality.

Among her other accomplishments, Alice Paul was one of the organizers the Women’s Suffrage Parade of 1913.

In her fight for women’s equality, Alice Stokes Paul and her friend Lucy Burns founded the National Woman’s Party and the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. They were adamant that a new narrative about where women belonged be written; therefore, in The Suffragist, their newsletter, women were characterized as powerful, competent, and confident.

Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns was born July 28, 1879, into an Irish Catholic New York family.

In 1890, Burns attended Packer Collegiate Institute, known at that time as the Brooklyn Female Academy. Beforebecoming an English teacher, Burns also attended Columbia University, Vassar College and Yale University. She taught high school for two years, but what she really wanted to do was further her own education. Her father, Edward Burns, supported that idea, so, in 1906, Lucy left the States and moved to Germany, where she studied until 1909.

After that, she moved to the United Kingdom to study English at Oxford. In the UK, she met Adela Pankhurst, her daughters and other activists. She became involved in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the fight for women’s rights, participated in demonstrations and became an organizer.

The actions of all of these committed women resulted in numerous arrests for “disorderly conduct,” newspaper reports, “setting an extremely bad example” and getting harsher sentences. While arrested, they damaged the cells, went on hunger strikes, refused to do prison work and organized more women to get involved.

Lucy and Alice met when they were both under arrest. They realized they were kindred spirits, both tired of the slow progress the movement was making in the States. In 1912, they decided to go back home and work together.

One of the editors of The Suffragist newsletter, Lucy founded the first permanent headquarters for suffrage work in Washington, D.C., alongside Alice Paul.

They worked together to plan the Woman Suffrage Procession on March 3, 1913 – the day before Woodrow Wilson’s first inauguration.

Over her lifetime, Lucy led the most of the picket protests and spent the longest time behind bars of any American suffragist.

“I don’t want to do anything more. I think we have done all this for women, and we have sacrificed everything we passed for them, and now let them fight for it now. I am not going to fight anymore.”

Burns was 87 when she made her transition on December 22, 1966.

Women’s Equality

Alice Paul and Lucy Burns acquired aggressive protest strategies while in England – like picketing and hunger strikes. After joining the women’s suffrage movements there, they joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1912, after returning to the United States; Paul led the Washington, D.C. chapter.

The problem was Paul preferred to urge Congress for a constitutional amendment, whereas NAWSA largely concentrated on state-by-state initiatives. Due to these disagreements, Paul and others left NAWSA and founded the National Woman’s Party.

Relative Success

The National Woman’s Party, campaigned against President Woodrow Wilson’s refusal to support women’ssuffrage. They organized hunger strikes and were jailed in order to secure the 19th Amendment.

As a result of the years of work by the suffragists, the House Committee on Suffrage made a decision on January 10, 1918, passing the amendment by a vote of 274 to 136. Burns and the women of the NWP immediately began work to secure the 11 additional votes they would need for the amendment to pass in the Senate. However, on June 27, 1918, the Senate narrowly failed to pass the amendment.

It was again introduced in the House in the 66th Congress (1919–1921). This time, it passed – on May 21, 1919 – by a vote of 304 to 90. The Senate concurred shortly afterward. The Nineteenth Amendment then went to the states, where it was finally ratified in August 1920.

The Nineteenth Amendment was passed by Congress June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 18, 1920. It granted women the right to vote. After decades of struggle, it guarantees women the right to vote.

In 1920, after the 19th Amendment was secure, Alice Paul wrote and worked for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), introducing the bill in 1923. She not only devoted the rest of her life to the passage of the ERA, but she contributed significantly to adding protection for women to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Equal Rights Amendment

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

The Equal Rights Amendment

Every Congress session since 1923 has seen lawmakers introduce the ERA, but until the 1970s, little was accomplished. The fact that Congress was predominately made up of men for the majority of the 20th century didn’t help. Only 10 women held Senate seats in the nearly five-decade period between 1922 and 1970, with no more than 2 holding concurrent seats. In the House, the image was only marginally better.

Reps. Martha Griffiths (D-MO) and Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) were among a new group of female lawmakers who pushed for the ERA to be given top legislative priority in 1970. Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-NY), the influential chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, had resisted holding a hearing on the ERA for more than 30 years, and they had to get past his opposition. Celler finally gave in when the pressure mounted. Bipartisan support helped the amendment pass both chambers of Congress in March 1972, far exceeding the two-thirds majority that the Constitution requires. The proposed amendment was immediately sent to the states for ratification with a seven-year window.

The amendment next needed to be ratified by 38 states, then it could be incorporated into the U.S. Constitution. The ratification procedure’s deadline was originally set at seven years, but lawmakers later added another three years to it.

The 38-state threshold was finally met in 2020, when Virginia ratified the amendment – over four decades after the deadline had passed. The Justice Department under the former President Donald Trump’s administration declared it would not be possible to remove the expired deadline to ratify the amendment because the time allowed had expired.

The current President, Joe Biden, has not taken any action to overturn the Justice Department’s determination.

The ERA has not been ratified (after nearly 100 years). It is still not part of the United States Constitution.

Alice was once asked why she persevered so deliberately; she answered with a quote from her father: “When you put your hand to the plow, you can’t set it down until you get to the end of the row.”

Alice Paul passed on July 9, 1977. We have clearly not reached the end of the row.

“It’s time to clear the path to equality.”

Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin.

sk.

Resources

Brennan Center for Justice, Article: The Equal Rights Amendment Explained, by Alex Cohen and Wilfred U. Codrington, III, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/equal-rights-amendment-explained

Disability Rights, Education and Defense Fund (DREDF), Article: Short History of the 504 Sit-in, by Kitty Cone,https://dredf.org/504-sit-in-20th-anniversary/short-history-of-the-504-sit-in/

Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Article: Alice Paul, Schlesinger Library/Collection,https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/schlesinger-library/collections/alice-paul

Huffpost, Article: Judith Heumann, ‘Mother of the Disability Rights Movement,’ Has Died, by Shruti Rajkumar, Mar 4, 2023, 7:51 PM EST, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/judith-heumann-obit-disability-rights-movement_n_6403ca28e4b029d870168df0

Ms. Magazine, Article: Fifty Years Later, the Equal Rights Amendment Is Ratified. Now What?, by Carrie N. Baker, 2/10/2022, https://msmagazine.com/2022/02/10/equal-rights-amendment-ratified/

PBS, American Experience, Article: Fannie Lou Hamer, From the Collection: Women in American History,https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/freedomsummer-hamer/

The New York Times, Article: Judy Heumann, Who Led the Fight for Disability Rights, Dies at 75,by Alex Traub, March 5, 2023, 6:26 PM EST, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/05/obituaries/judy-heumann-dead.html

USA TODAY, Article: ’It’s time to clear the path to equality’: Senate revisits Equal Rights Amendment after 40 years, by Rachel Looker, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2023/03/05/senate-ratify-equal-rights-amendment-era/11389985002/

Wikipedia, Article: Fannie Lou Hamer, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fannie_Lou_Hamer

Wikipedia, Article: Judy Heumann, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_Heumann

Women’s History.org, Article: Alice Paul (1885-1977), edited by Debra Michals, PhD, 2015,https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/alice-paul

Image: A Suffragette on Hunger Strike in the UK Being Force Fed with a Nasal Tube

Date: Circa 1911, Source: Sylvia Pankhurst (1911). The Suffragette: The History of the Women’s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905 – 1910. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company, facing p. 433. Author: Unknown (Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70354309)

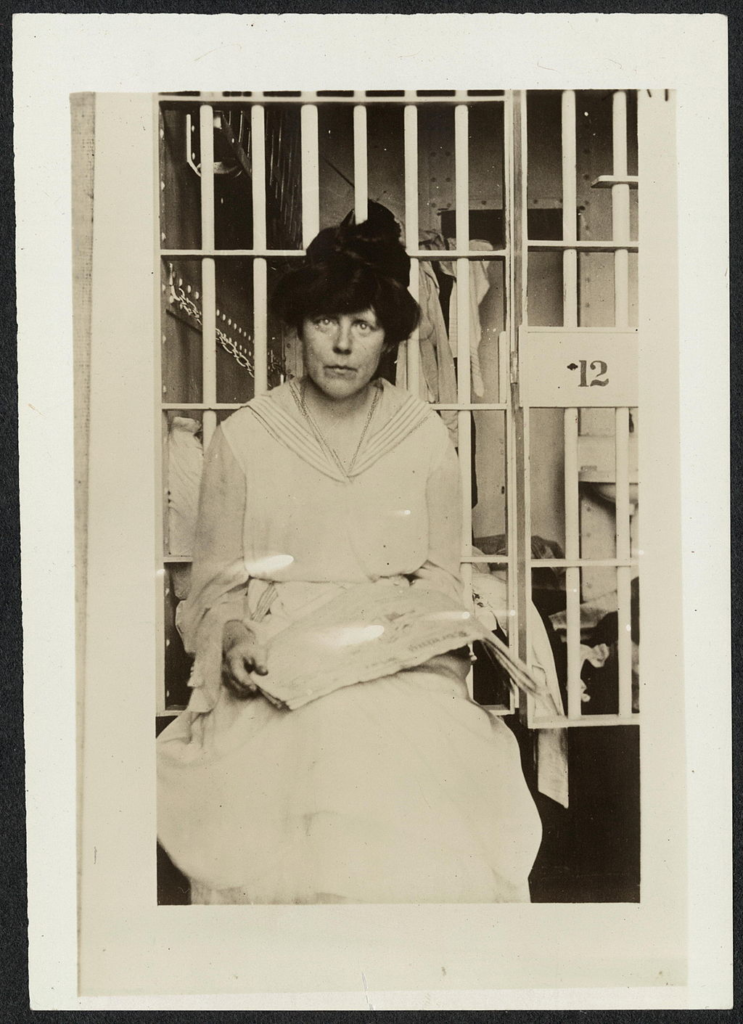

Image: Miss [Lucy] Burns in Occoquan Workhouse, Washington

Date: 1917 November, Author: Harris & Ewing, Washington, D.C. (Photographer), Informal portrait, Lucy Burns, ¾ length, seated, facing forward, holding a newspaper in her lap, in front of a prison cell, likely at Occoquan Workhouse, in Virginia

Image: [Alice] Paul Toasting (with grape juice) the Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 26, 1920

By Harris & Ewing, Inc. – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3a21383.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2556292

Image: Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer, American civil rights leader, at the Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City, New Jersey, August 1964. Leffler, Warren K., photographer. Photograph shows half-length portrait of Hamer seated at a table. No known restrictions on publication. https://lccn.loc.gov/2003688126